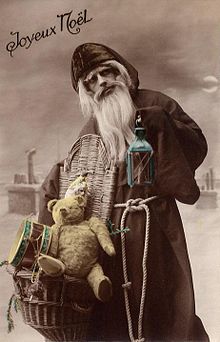

We’re all familiar with the concept of a jolly, white-bearded man in a red suit who flies through the skies on Christmas Eve delivering presents to all the good boys and girls around the world. No matter how you picture him, Santa Claus, aka Father Christmas or Saint Nicholas, is a familiar figure at Christmas time. This image, taken by me a couple of years ago shows a Victorian Santa.

But did you know that today’s Santa has pagan origins, too?

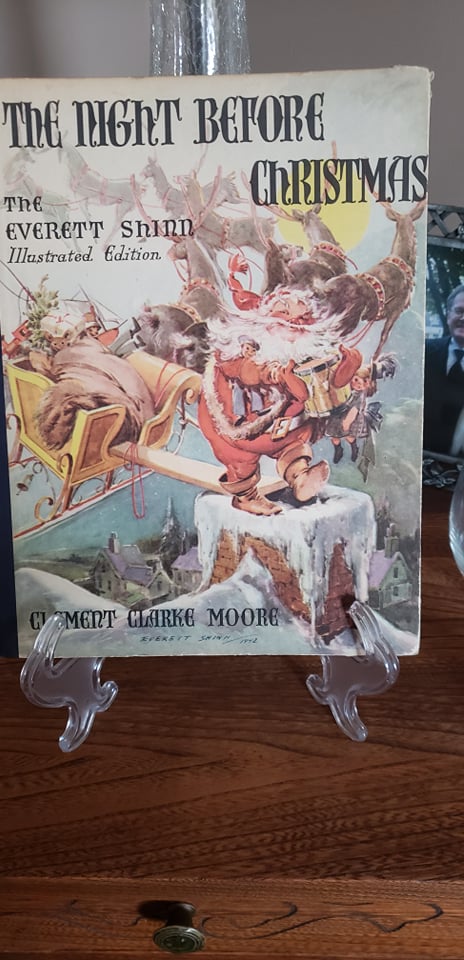

Odin atop his eight-legged steed, Sleipnir. In pagan times the pair would ride at Yule, terrifying those who dared to be out but also bringing candy and toys to children. Clement C. Moore replaced Sleipnir with eight flying reindeer in his 18th-century poem, and the image stuck.

Much of the information in today’s post is credited to Judith Gabriel Vinje from Los Angeles who posted parts of this in an article for the Norwegian American in December 2014.

The belief in a beared man flying through the night sky most likely dates back to the Norse and Germanic mythology. The various people of Northern Europe celebrated a holiday called Yule, which took place midwinter around the winter solstice. In many ways, Santa may owe his very existance to the Norse god Odin, but he’s certainly changed over the years, changing not only his appearance but going from a powerful and terrifying Viking god to a fat, jolly good natured man.

The next few paragraphs are taken directly from the article.

Odin was chief among the Norse pagan deities. (We still remember him in the day of the week named for him, Wednesday, Woden’s Day.) He was spiritual, wise, and capricious. In centuries past, when the midwinter Yule celebration was in full swing, Odin was both a terrifying specter and an anxiously awaited gift-bringer, soaring through the skies on his flying eight-legged white horse, Sleipnir.

Back in the day of the Vikings, Yule was the time around the Winter Solstice on Dec. 21. Gods and ghosts went soaring above the rooftops on the Wild Ride, the dreaded Oskoreia. One of Odin’s many names was Jólnir (master of Yule). Astride Sleipnir, he led the flying Wild Hunt, accompanied by his sword-maiden Valkyries and a few other gods and assorted ghosts.

The motley gang would fly over the villages and countryside, terrifying any who happened to be out and about at night. But Odin would also deliver toys and candy. Children would fill their boots with straw for Sleipnir, and set them by the hearth. Odin would slip down chimneys and fire holes, leaving his gifts behind. Sound familiar?

With the advent of Christianity, participating in any pagan celebrations was forbidden. Yule was changed to a celebration of the birth of the Christ child and Odin gradually faded from the picture and the celebration.

The first person to take Odin’s place was St. Nicholas, a Greek bishop from the 4th century, usually dressed in a flowing red cloak. He became the patron saint of gift-giving in most parts of the world, but not in Scandinavia.

In many parts of Scandinavia, including Norway, neither St. Nicholas nor Santa Claus are the most common Christmas gift-giving icons. That honour belongs to julenisse, a creature found in Scandinavian folklore, a nisse, called a tomte in Sweden, is a gnome-like, short creature with a long white beard and a red hat. Nisse were a lot like the elves who helped the shoemakker in the fairy tale. During the year, they helped farmers with their chores, but on Christmas Eve they entered the houses through the front door and left gifts for the family. But Nisse were temperamental creatures, and if the family forgot to leave him bowl of porridge with butter in it on Christmas Eve — the spirit might turn against his friends and that could be a lot worse than a lump of coal in a stocking.

With the Reformation, Saint Nick and all the other sainbts were pushed aside in most places but not in the Netherlands. There he became Sinterklaas, a wise old man with a white beard, white dress, and red cloak who surprisingly rode thtough the skies on his magical eight-legged white horse, delivering gifts down the chimney to the well-behaved children on Dec. 6, also known as St. Nicholas Day. Do you see the mixing of pagan and Christian traditions here? He arrives with his helper Zwarte Piet who keeps track of all the good girls and boys.

Time passed and when the Europeans came to North America, they brought their traditions with them. While the Dutch brought Sinterklass, the English Father Christmas, the French brought Père Noël or Papa Noël who came down from the heavens and delivered toys and gifts. Before going to bed on Christmas Eve, children would fill their shoes with carrots and treats for Père Noël’s donkey, Gui, the French word for Mistletoe. Père Noël would accept the food and replace it with gifts small enough to fit inside the shoes. In some parts of France, notably Alsace and Lorraine, Belgium, Switzerland, and some areas in Eastern Europe, on December 6, Le Père Fouettard, a sinister figure clothed in black travels with St. Nicholas and spanks those boys and girls who’ve misbehaved throughout the year. I grew up in a French Canadian home with Père Noël although mine looked a lot like my English friends’ Santa Claus.

Today, much of the tradition we associate with Santa Claus comes from the poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas” by Clement C. Moore. Odin and Sinterklaas’s eight-legged horse has morphed into eight flying reindeer–nine if you add Rudolph. The nisse have become elves who work at the North Pole making toys, and Santa eats milk and cookies, not buttered porridge.

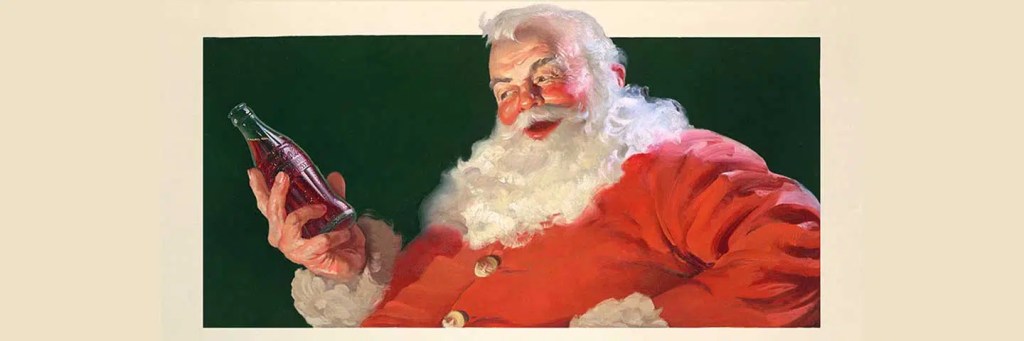

Today’s image of Santa owes a lot to the Coca-Cola company advertizing. In 1931, they gave us the image of the jolly, old elf we are most familiar with.

For years now, I’ve collected various Santas. He changes from year to year and country to country, but in the end, he still brings joy and laughter, candy and gifts, to children everywhere.

So there you have it. Come back tomorrow to see what new fact I’ll have to share.